View the full episode transcript.

On hot days, fourth-grader Adriana Salas has observed that when the sun beats down on the pavement in her schoolyard it “turns foggy.” There are also days where the slide burns the back of her legs if she is wearing shorts or the monkey bars are too hot to touch. Salas, who attends Roosevelt Elementary School in San Leandro, California, is not alone in feeling the effects of heat on her schoolyard. Across the country, climbing temperatures have led schools to cancel classes and outdoor activities to protect students from the harmful effects of the heat.

Jenny Seydel, an environmental educator and founder of Green Schools National Network, encourages teachers to leverage students’ observations about their schools to make learning come alive. According to Seydel, when teachers use the school grounds as a way to learn about social issues, they’re using their school as a three-dimensional textbook. For example, schools’ energy and water conservation, architecture and lunches are rich with potential for project-based learning. “We can learn from a textbook. We can memorize concepts. We can use formulas, but we don’t incorporate that learning until it is real,” said Seydel.

Against the backdrop of climate change, Roosevelt Elementary School teachers turned to their schoolyards as a way to apply lessons about rising temperatures to the real world. While these issues can seem overwhelming to young students, exploring them within the context of their school can not only make lessons stick, but also encourage students’ sense of civic agency.

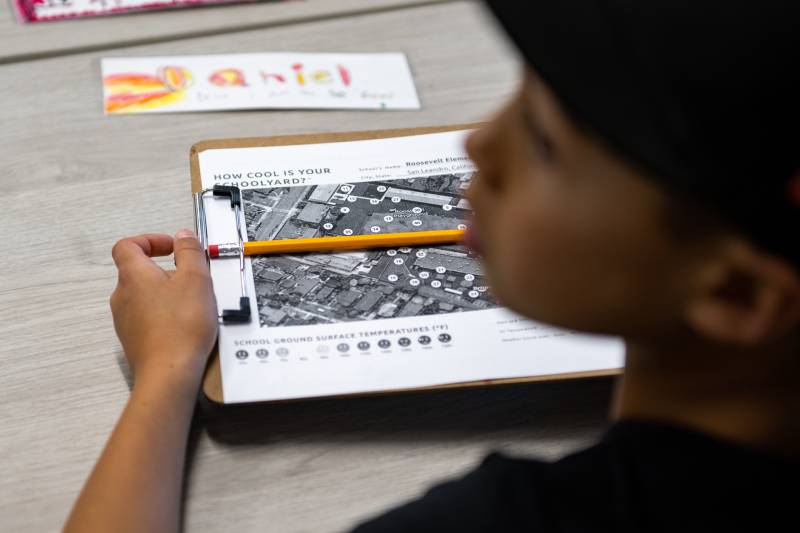

Armed with infrared thermometers and a map of their school, fourth graders at Roosevelt embarked on the “How cool is your school?” project created by Green Schoolyards America, an organization that works to transform asphalt-laden schoolyards into greener spaces. The guiding questions for the fourth graders were:

Fourth grade teacher Nicole Lamm prepares students for a temperature mapping activity in the schoolyard at Roosevelt Elementary School in San Leandro, California. (Beth LaBerge/ KQED)

In groups of three, students of Dorie Heinz and Nicole Lamm classes measured and recorded the ground temperature at 25 locations around their school. As students gathered data from places like the tetherball courts, lunch area, and parking lot, a pattern emerged: materials matter. For example, one group found that the ground temperature they recorded at the main playground, which was made of rubber safety material, was almost 50 degrees hotter than the temperature they measured at their school’s grass playing field.

Jake Council (from left), Arlo Jones and Adrianna Salas participate in a temperature-mapping activity in the schoolyard at Roosevelt Elementary School in San Leandro on June 1, 2023. Students used an infrared thermometer to record temperatures in locations around the playground and yard, including asphalt and green spaces, as an opportunity to learn about climate change, sustainability and other academic topics through hands-on experience. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

“Our school districts are one of the largest land managers,” Lamm explained to students. “Most schools are covered in asphalt and other materials that heat up in the sun, and schools generally have a lack of shade.”

According to preliminary research by Green Schoolyards America, over two million students in California attend schools with less than 5% tree canopy. Less tree coverage contributes to urban heat island effect, which is when heat-absorbing materials like asphalt or tar result in higher temperatures in a community. Students’ firsthand observations provided a tangible link between their immediate surroundings and issues outside of their school.

When the students returned from gathering data, they shared their findings as a class. When students presented the temperatures they measured, Lamm recorded it on a poster-sized map of the school with color coded stickers. Blue stickers represented the lowest temperatures, which were below 70 degrees fahrenheit, while red stickers represented temperatures above 100 degrees fahrenheit. Shades of yellow and orange stickers indicated temperatures in between.

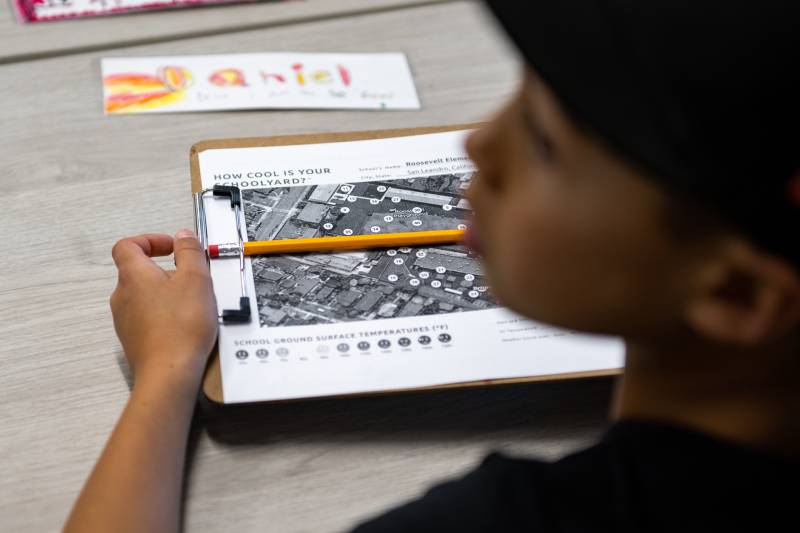

A student sits with a map of their school in preparation for the temperature-mapping activity. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

Looking at the map, students pointed out the greater volume of red stickers, compared with blue ones. “It’s mostly hot where we’re playing,” said Adriana. The two lonely blue stickers were in areas with a large tree and a shade structure, respectively.

Lamm and Heinz prompted students to brainstorm how to make the playground cooler. “We want to mark our map with triangles to show where we think we should plant more trees and squares for where we think we need shade structures,” said Heinz. One student offered an idea to protect their schools’ youngest students. “There’s this little concrete box. I was thinking maybe we could plant a tree because sometimes I would notice kindergartners eating a snack there,” he said. By the end of the activity, the map was covered in colored dots. Triangle and square-shaped stickers – students’ proposals for shade – were next to some of the hottest areas. The teachers posted the map with all of its stickers in front of the school to show their findings to parents and community members.

Teacher Dorie Heinz places stickers on the schoolyard map as students brainstorm how to make the playground cooler. By the end of the activity, the map was covered in colored dots. (Ki Sung/KQED)

Tackling larger issues at the school level can nurture problem-solving skills that extend beyond academic subjects and prepare students for the complexities of the larger world. “It’s really depressing for a lot of kids to read about all the negative things that climate change has created in the world,” said Sharon Danks, CEO and founder of Green Schoolyards America — the organization that created the “How Cool is Your School” activity. In offering this hands-on STEM lesson plan to schools, Danks and her team hope that administrators implement students’ suggestions and create green schoolyards. “It gives kids a chance to learn about climate change, but also learn about being positive forces for change for the better,” she said.

While green schoolyards can vary widely because they reflect the surrounding ecosystem and climate, they may include features such as edible gardens, stormwater capture features or walking trails. Danks described a green schoolyard as “an ecologically rich park and a place that has all kinds of things happening and all types of different social niches for people to be doing different activities in different places and in a natural environment filled with plants and living things.”

Green schoolyards offer protection against the heat and provide a unique setting for interdisciplinary learning experiences, according to Priya Cook from Children & Nature Network, an organization that works to ensure kids have equitable access to green spaces. She adds that benefits associated with outdoor learning, such as improved behavioral control and increased student engagement, “impact the way a kid can thrive in the classroom.” When students have access to a green schoolyard, their physical activity increases, and studies have shown that being in natural spaces improves mental health and wellbeing.

While green schoolyards boast a lot of benefits, not every school can easily make the transformation. Danks cited failures to pass bills supporting greening projects and a shortage of funds as the most significant obstacles. Removing asphalt is costly. And because green space is inequitably distributed, schools with the most asphalt are also likely to be schools with the least financial resources. However, California has allocated $150 million for green schoolyards, and other states may follow suit.

As one of the most heavily trafficked public spaces, green schoolyards could have an outsized effect. “There’s a reframing that needs to happen in our budget, in our mindset, that says this is a crucial space for children,” said Danks.

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Kara Newhouse: Welcome to MindShift, the podcast about the future of learning and how we raise our kids. I’m Kara Newhouse.

Nimah Gobir: And I’m Nimah Gobir. Educators are always striving to create hands-on lessons to engage students. These types of learning approaches improve learning retention and promote a deeper understanding of concepts.

Kara Newhouse: Some teachers rely on project based learning, where they have students solve real problems in their community. Others might opt for experiential learning, which can involve field trips and role-playing. There’s also collaborative learning where students work with peers.

Nimah Gobir: Luckily, teachers don’t have to go far if they want to implement hands-on approaches. According to educator Jenny Seydel, the school building and school grounds are incredible resources for this type of learning.

Jenny Seydel: For children up through middle school, that is the place that they spend most time. By the time a child graduates from high school, they’ve spent more than 15,000 hours in a school.

Nimah Gobir: Jenny is an expert in environmental education and the founder of Green Schools National Network. She invites educators to think of schools as 3-dimensional textbooks.

Jenny Seydel: Any phenomenon, even historical phenomenon, can be taught through the history of that particular school — the social issues and social problems that are happening in the world — are oftentimes happening in a school. That’s the place where we can bring anything to life that we are teaching.

Kara Newhouse: So Jenny is saying we can use schools to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and real-world application?

Nimah Gobir: That’s exactly right. When you use your school as a 3D textbook, you can look at all kinds of things – like your school’s water system or architecture, even school lunches. Today we’ll zero in on schoolyards.

Nimah Gobir: If you think about it. Schoolyards are incredible because they entertain kids over many years and developmental stages. And unless a kid is part of a family that is big on gardening, hiking or camping, then it’s likely that schoolyards are where they spend the most of their outside time.

Sharon Danks: My name is Sharon Danks, and I’m an environmental city planner.

Nimah Gobir: I talked to Sharon to learn more about schoolyards – how they’re used and their untapped potential.

Sharon Danks: Many things they would like to study can be done outdoors in a schoolyard. These days, it’s particularly well-suited to studying climate change and how the materials that people put into the environment shift the temperatures of our urban locations. In California, we have 130,000 acres of public land at our K-12 schools. And they have close to 6 million people on them every day. And that’s more public land visitation than, say, Yosemite has in an entire year.

Nimah Gobir: But unlike Yosemite and other national parks the majority of schoolyards are not very green!

Sharon Danks: Asphalt, plastic, grass and rubber, which are a lot of the go to traditional materials in the United States.

Kara Newhouse: I’ve seen asphalt and blacktop at many schools. It’s usually where kids play four-square and skin their knees playing tag!

Nimah Gobir: It’s everywhere. In fact, millions of kids go to schools where fewer than five percent of the grounds have trees.

Sharon Danks: Even in communities that have a lot of trees, if you look at the aerial photos, they’re not at the schools.

Nimah Gobir: If a school has trees or green space it is usually around the edges of a school. Like next to the school sign or by the parking lots. It’s not to shade kids in sunny weather.

Nimah Gobir: And these days kids need all the shade they can get. Triple digit temperatures have forced schools all around the country to cancel classes and even delay the first day of school. Here’s what 4th grader Adriana Salas is noticing.

Adriana Salas: It’s mostly hot where we’re playing at. And sometimes when it’s too hot, sometimes when you look like, just on the top of anything it turns like foggy.

Nimah Gobir: She’s talking about when it gets so hot out that the ground looks kind of wavy. She’s seen that happen on her school’s playground. We’ll hear more from Adriana later.

Priya Cook: There’s a lot of communities struggling with urban heat island effect and really extreme temperatures that make it unsafe for kids to be outside.

Nimah Gobir: This is Priya Cook from the Children & Nature Network organization.

Kara Newhouse: I heard Priya say “urban heat island effect.” What is that?

Nimah Gobir: That’s when asphalt and pavement actually increase the temperature in a community.

Priya Cook: There’s a lot of materials that are used in playgrounds that we use in parking lots and roads that really absorb heat and reflect that heat back.

Nimah Gobir: Places that have a lot of urban heat islands are likely to be lower income parts of the city because they usually have fewer plants and more pavement. Often these hotter areas are populated by folks of color.

Priya Cook: There’s a difference in some cases of ten degrees between a place that has trees planted and a site that does not. And so that’s in many cases, that’s a big enough difference to, dictate whether or not kids are going to go outside that day, which has all kinds of health and learning impacts.

Nimah Gobir: The good news is that schools aren’t standing idly by while their schoolyards heat up. We’ll hear from one school in San Leandro, California about how they turned to their schoolyards as a way to learn more about these environmental changes firsthand. That’s coming up after the break.

Nimah Gobir: Stay with us.

Nicole Lamm: Welcome, everybody.

Nimah Gobir: It’s a beautiful day at Roosevelt Elementary School in San Leandro, California. Today it’s 67 degrees fahrenheit, but temperatures here can get into the triple digits. Ms. Heinz and Ms. Lamm’s 4th grade classes have come together to start a project that uses their schoolyard as a 3D textbook.

Nicole Lamm: Today is our first day of doing our “How Cool is Your School?” project.

Nimah Gobir: Ms. Lam is speaking to students using a headset. This project is the brainchild of Green Schoolyards America — Sharon Danks, who we spoke to earlier is the founder of that organization. Ms. Lamm teed up students for the “How Cool is Your School?” project with two guiding questions…

Nicole Lamm: Is our school a comfortable place for children and adults when the weather is warm?

Nimah Gobir: And…

Nicole Lamm: How can our school community take action to shade and protect students from rising temperatures due to climate change?

Nimah Gobir: Students are put into groups of three and each group is given a map of the school

Nicole Lamm: We have our classrooms right here. We have the basketball court, the cafeteria, our other building over there and the kindergarten rooms…

Nimah Gobir: Different locations on the map are numbered from one to 25

Nicole Lamm: Those numbers are there for a reason. You are going to get five places that you have to measure. So you have to figure out exactly where that number is and find that spot in the school.

Nimah Gobir: Each group also gets an infrared thermometer.

Dorie Heinz: You’re going to point the thermometer at the ground. When you pull the trigger, the temperature stops and records it. That’s where you and your team are going to record your temperature. So, at one location you’ll be doing three readings.

Nimah Gobir: This is the crux of the project, so I’ll reiterate what Ms Lamm says: Each group takes three temperature readings of the same point on the ground in their assigned location. This is to get an accurate reading of the ground surface. Then, they record the average of the three readings on a worksheet.

Adrianna Salas: We are going on the field to 16.

Nimah Gobir: We followed one group of students as they did their measurements.

Arlo Jones: Arlo Jones, fourth grade.

Jake Decker: Jake Decker, fourth grade.

Adriana Salas: Adriana Salas, fourth grade.

Nimah Gobir: And yes, that is the same Adriana we heard from earlier!

Nimah Gobir: First up on their list: area 16. It’s located on the field, so it’s a grassy area. They make their way over and get their three readings with the thermometer

Nimah Gobir: They record their findings. The surface of the field has an average of about 97 degrees. They head to the next spot on their list. Number 17 on the map. It has grass too and it’s close to some classrooms.

Nimah Gobir: So the average temperature of the ground surface here is about 95 degrees. They start to make their way to their third location: number 18. It’s a triangular playground area with swings.

Arlo Jones: I would say it’s like the main playground. The main place where people play.

Adriana Salas: It’s like the big playground

Nimah Gobir: They describe it as the school’s main playground so most kids play there. The surface is made of that rubber safety material that you see in so many schoolyards now. Especially newer schools…and they predict that it’s going to be hot. They’re right. The three readings they get there average at a steamy 143 degrees

Nimah Gobir: Adriana shared some reflections on what she’s learned about her schoolyard so far.

Adriana Salas: It’s very hot. And sometimes you might get like, a shocking, like, “Wow. Like kids play in the hotness.”

Nimah Gobir: After students are finished visiting all of the locations they’ve been assigned, they come back to the classroom to talk about their findings.

Nicole Lamm: So when we say a location that you tested, I want you to raise your hand and read out the average that you just found for location one.

Nimah Gobir: That’s Ms. Lamm again. The other teacher, Miss Heinz, is standing in front of a poster-sized map of the school. She has colored stickers ranging from blue – which represent temperatures in the 70s or below – to deep shades of red, which represents temperatures over 100 degrees.

Nicole Lamm: Location two right over here where the tetherball is. 115.

Nicole Lamm: What about location three? Right on the lake by the four square. 123.

Nicole Lamm: Four, which is over by where you eat lunch every day? 63.

Nicole Lamm: What do we notice about location four? It’s covered by a shade structure? And can you say that number nice and loud one more time? Sixty-three degrees is a lot cooler when we have a shaded structure. Interesting to notice.

Nimah Gobir: Every time they call out a number, a colored sticker representing the temperature is stuck to the corresponding location on the big version of the map.

Kara Newhouse: So students could actually see where the different colored dots were clustered at their school.

Nimah Gobir: They went all the way through 25 locations. And when they were all done calling out the average temperatures. They were asked to share what they noticed about all the colored dots on the map.

Nicole Lamm: What do you notice about the two places that are blue, though?

Students: They’re shaded.

Dorie Heinz: They’re shaded so they’re way cooler.

Nicole Lamm: What? Shades the blue dot on this side?

Students: The tree.

Nicole Lamm: What about the other one? The canopy. The shade structure. So both of those are the coolest locations and we know that they have things that are providing shade: the trees and the shade structure. Really good observation.

Nimah Gobir: Aside from those two blue spots the school is mostly a cluster of red and yellow dots representing ground surface temperatures from 80 degrees to as high as 151 degrees. The really hot temperatures are on the playgrounds and basketball courts. Materials like turf, rubber and blacktop receive temperatures in the triple digits.

Nimah Gobir: But the project doesn’t end there.

Kara Newhouse: What else do they do?

Nimah Gobir: A big part of using your school as a 3D textbook, especially when dealing with big issues like climate change, is finding solutions and encouraging student agency. So for the last part of the activity, students make a proposal for how they can make the school a bit cooler. So Ms. Lamm directs the students’ attention back to the big map again.

Nicole Lamm: We want to mark our map with triangles to show where we think we should plant more trees and squares for where we think we need shade structures.

Nimah Gobir: You can hear that they’re thinking about the schoolyards materials as they decide which places need cooling down.

Nicole Lamm: So Adriana is saying that not just because of the ground surface material, but because of the playground itself that could benefit from having a shade structure over it. Is that right?

Adriana Salas: Because the play structure is made out of metal. Metal is really easy to get hot

Nicole Lamm: Right. Thinking about that material again. The play structure is made out of hard plastic and metal. Those things get really really hot. So we definitely want to add a shade structure over the playground. I love that idea. I also heard Adriana say that we want to add a tree to the middle of the field similar to how it looks at the front of the school with our big trees.

Nimah Gobir: When they were done, they put the big map with all of its stickers on display in the front of the school for parents and community members to see.

Kara Newhouse: Sometimes talking about real-world challenges can lead to anxiety and feelings of helplessness, but it’s great that they were able to share their insights. That’s often the first step towards putting ideas into action.

Nimah Gobir: Activities like this can lead to schools developing green schoolyards. Here’s Sharon Danks again to tell us more.

Sharon Danks: I would say that it is most succinctly described as an ecologically rich park.

Nimah Gobir: They vary widely. The plants in a green schoolyard will depend on its ecosystem and climate. A lot of schools are starting to transition to green schoolyards.

Sharon Danks: I think the need is becoming more clear through weather getting more extreme.

Nimah Gobir: California is in the second year of a statewide initiative called the California Schoolyard Forest System. The main goal is to increase the number of trees in public schools.

Nimah Gobir: Green schoolyards don’t just provide shade on hot days. They come with a whole bunch of benefits, including more opportunities for kids to use their schools for learning. When school leaders start dreaming about the potential they can unlock with a green schoolyard, it’s hard to stop. They start saying things like…

Sharon Danks: I’d like a place for kids to do their curriculum outside. I’d like a place that’s good for physical and mental health for kids and teachers. We’d like a place for nature. We’d like a place for the birds to come, the wildlife, to be able to visit the pollinators andyou want to see the butterflies and you know, things like that.

Nimah Gobir: Our school buildings and schoolyards are not just physical spaces but dynamic learning resources waiting to be tapped into.

Kara Newhouse: Learning from textbooks is valuable, but true learning comes alive when we bring education into the real world. School grounds and schoolyards provide the perfect opportunity to do just that.

Nimah Gobir: And if a school is able to develop a green schoolyard, you can provide kids with a living laboratory where they engage with nature, explore ecosystems, and understand the impact of their actions on the environment.

Nimah Gobir: So teachers, you don’t have to travel far for your next hands-on learning opportunity. Seeing your schoolyards and school buildings in a new light might just empower the next generation of change-makers.

Adriana Salas: I think I think now I’m going to be really good – an expert!

Nimah Gobir: This episode would not have been possible without Sharon Danks, Jenny Seydel, Priya Cook, Principal Kumamoto, Ms. Lamm, Ms. Heinz, and their 4th graders. A big thank you to Kevin Stark and Laura Klivans for their support with reporting.

Nimah Gobir: The MindShift team includes Ki Sung, Kara Newhouse, Marlena Jackson Retondo and me, Nimah Gobir. Our editor is Chris Hambrick and Seth Samuel is our sound designer.

Nimah Gobir: Additional support from Jen Chien, Katie Sprenger, Cesar Saldaña and Holly Kernan .

Nimah Gobir: MindShift is supported in part by the generosity of the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation and members of KQED.

Nimah Gobir: Thank you for listening!

Continue reading...

On hot days, fourth-grader Adriana Salas has observed that when the sun beats down on the pavement in her schoolyard it “turns foggy.” There are also days where the slide burns the back of her legs if she is wearing shorts or the monkey bars are too hot to touch. Salas, who attends Roosevelt Elementary School in San Leandro, California, is not alone in feeling the effects of heat on her schoolyard. Across the country, climbing temperatures have led schools to cancel classes and outdoor activities to protect students from the harmful effects of the heat.

Jenny Seydel, an environmental educator and founder of Green Schools National Network, encourages teachers to leverage students’ observations about their schools to make learning come alive. According to Seydel, when teachers use the school grounds as a way to learn about social issues, they’re using their school as a three-dimensional textbook. For example, schools’ energy and water conservation, architecture and lunches are rich with potential for project-based learning. “We can learn from a textbook. We can memorize concepts. We can use formulas, but we don’t incorporate that learning until it is real,” said Seydel.

Against the backdrop of climate change, Roosevelt Elementary School teachers turned to their schoolyards as a way to apply lessons about rising temperatures to the real world. While these issues can seem overwhelming to young students, exploring them within the context of their school can not only make lessons stick, but also encourage students’ sense of civic agency.

A schoolyard becomes a learning arena

Armed with infrared thermometers and a map of their school, fourth graders at Roosevelt embarked on the “How cool is your school?” project created by Green Schoolyards America, an organization that works to transform asphalt-laden schoolyards into greener spaces. The guiding questions for the fourth graders were:

- Is our school a comfortable place for children and adults when the weather is warm?

- How can our school community take action to shade and protect students from rising temperatures due to climate change?

Fourth grade teacher Nicole Lamm prepares students for a temperature mapping activity in the schoolyard at Roosevelt Elementary School in San Leandro, California. (Beth LaBerge/ KQED)

In groups of three, students of Dorie Heinz and Nicole Lamm classes measured and recorded the ground temperature at 25 locations around their school. As students gathered data from places like the tetherball courts, lunch area, and parking lot, a pattern emerged: materials matter. For example, one group found that the ground temperature they recorded at the main playground, which was made of rubber safety material, was almost 50 degrees hotter than the temperature they measured at their school’s grass playing field.

Jake Council (from left), Arlo Jones and Adrianna Salas participate in a temperature-mapping activity in the schoolyard at Roosevelt Elementary School in San Leandro on June 1, 2023. Students used an infrared thermometer to record temperatures in locations around the playground and yard, including asphalt and green spaces, as an opportunity to learn about climate change, sustainability and other academic topics through hands-on experience. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

“Our school districts are one of the largest land managers,” Lamm explained to students. “Most schools are covered in asphalt and other materials that heat up in the sun, and schools generally have a lack of shade.”

According to preliminary research by Green Schoolyards America, over two million students in California attend schools with less than 5% tree canopy. Less tree coverage contributes to urban heat island effect, which is when heat-absorbing materials like asphalt or tar result in higher temperatures in a community. Students’ firsthand observations provided a tangible link between their immediate surroundings and issues outside of their school.

Nurturing curiosity and critical thinking

When the students returned from gathering data, they shared their findings as a class. When students presented the temperatures they measured, Lamm recorded it on a poster-sized map of the school with color coded stickers. Blue stickers represented the lowest temperatures, which were below 70 degrees fahrenheit, while red stickers represented temperatures above 100 degrees fahrenheit. Shades of yellow and orange stickers indicated temperatures in between.

A student sits with a map of their school in preparation for the temperature-mapping activity. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

Looking at the map, students pointed out the greater volume of red stickers, compared with blue ones. “It’s mostly hot where we’re playing,” said Adriana. The two lonely blue stickers were in areas with a large tree and a shade structure, respectively.

Lamm and Heinz prompted students to brainstorm how to make the playground cooler. “We want to mark our map with triangles to show where we think we should plant more trees and squares for where we think we need shade structures,” said Heinz. One student offered an idea to protect their schools’ youngest students. “There’s this little concrete box. I was thinking maybe we could plant a tree because sometimes I would notice kindergartners eating a snack there,” he said. By the end of the activity, the map was covered in colored dots. Triangle and square-shaped stickers – students’ proposals for shade – were next to some of the hottest areas. The teachers posted the map with all of its stickers in front of the school to show their findings to parents and community members.

Teacher Dorie Heinz places stickers on the schoolyard map as students brainstorm how to make the playground cooler. By the end of the activity, the map was covered in colored dots. (Ki Sung/KQED)

The power and potential for green schoolyards

Tackling larger issues at the school level can nurture problem-solving skills that extend beyond academic subjects and prepare students for the complexities of the larger world. “It’s really depressing for a lot of kids to read about all the negative things that climate change has created in the world,” said Sharon Danks, CEO and founder of Green Schoolyards America — the organization that created the “How Cool is Your School” activity. In offering this hands-on STEM lesson plan to schools, Danks and her team hope that administrators implement students’ suggestions and create green schoolyards. “It gives kids a chance to learn about climate change, but also learn about being positive forces for change for the better,” she said.

While green schoolyards can vary widely because they reflect the surrounding ecosystem and climate, they may include features such as edible gardens, stormwater capture features or walking trails. Danks described a green schoolyard as “an ecologically rich park and a place that has all kinds of things happening and all types of different social niches for people to be doing different activities in different places and in a natural environment filled with plants and living things.”

Green schoolyards offer protection against the heat and provide a unique setting for interdisciplinary learning experiences, according to Priya Cook from Children & Nature Network, an organization that works to ensure kids have equitable access to green spaces. She adds that benefits associated with outdoor learning, such as improved behavioral control and increased student engagement, “impact the way a kid can thrive in the classroom.” When students have access to a green schoolyard, their physical activity increases, and studies have shown that being in natural spaces improves mental health and wellbeing.

While green schoolyards boast a lot of benefits, not every school can easily make the transformation. Danks cited failures to pass bills supporting greening projects and a shortage of funds as the most significant obstacles. Removing asphalt is costly. And because green space is inequitably distributed, schools with the most asphalt are also likely to be schools with the least financial resources. However, California has allocated $150 million for green schoolyards, and other states may follow suit.

As one of the most heavily trafficked public spaces, green schoolyards could have an outsized effect. “There’s a reframing that needs to happen in our budget, in our mindset, that says this is a crucial space for children,” said Danks.

Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Kara Newhouse: Welcome to MindShift, the podcast about the future of learning and how we raise our kids. I’m Kara Newhouse.

Nimah Gobir: And I’m Nimah Gobir. Educators are always striving to create hands-on lessons to engage students. These types of learning approaches improve learning retention and promote a deeper understanding of concepts.

Kara Newhouse: Some teachers rely on project based learning, where they have students solve real problems in their community. Others might opt for experiential learning, which can involve field trips and role-playing. There’s also collaborative learning where students work with peers.

Nimah Gobir: Luckily, teachers don’t have to go far if they want to implement hands-on approaches. According to educator Jenny Seydel, the school building and school grounds are incredible resources for this type of learning.

Jenny Seydel: For children up through middle school, that is the place that they spend most time. By the time a child graduates from high school, they’ve spent more than 15,000 hours in a school.

Nimah Gobir: Jenny is an expert in environmental education and the founder of Green Schools National Network. She invites educators to think of schools as 3-dimensional textbooks.

Jenny Seydel: Any phenomenon, even historical phenomenon, can be taught through the history of that particular school — the social issues and social problems that are happening in the world — are oftentimes happening in a school. That’s the place where we can bring anything to life that we are teaching.

Kara Newhouse: So Jenny is saying we can use schools to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and real-world application?

Nimah Gobir: That’s exactly right. When you use your school as a 3D textbook, you can look at all kinds of things – like your school’s water system or architecture, even school lunches. Today we’ll zero in on schoolyards.

Nimah Gobir: If you think about it. Schoolyards are incredible because they entertain kids over many years and developmental stages. And unless a kid is part of a family that is big on gardening, hiking or camping, then it’s likely that schoolyards are where they spend the most of their outside time.

Sharon Danks: My name is Sharon Danks, and I’m an environmental city planner.

Nimah Gobir: I talked to Sharon to learn more about schoolyards – how they’re used and their untapped potential.

Sharon Danks: Many things they would like to study can be done outdoors in a schoolyard. These days, it’s particularly well-suited to studying climate change and how the materials that people put into the environment shift the temperatures of our urban locations. In California, we have 130,000 acres of public land at our K-12 schools. And they have close to 6 million people on them every day. And that’s more public land visitation than, say, Yosemite has in an entire year.

Nimah Gobir: But unlike Yosemite and other national parks the majority of schoolyards are not very green!

Sharon Danks: Asphalt, plastic, grass and rubber, which are a lot of the go to traditional materials in the United States.

Kara Newhouse: I’ve seen asphalt and blacktop at many schools. It’s usually where kids play four-square and skin their knees playing tag!

Nimah Gobir: It’s everywhere. In fact, millions of kids go to schools where fewer than five percent of the grounds have trees.

Sharon Danks: Even in communities that have a lot of trees, if you look at the aerial photos, they’re not at the schools.

Nimah Gobir: If a school has trees or green space it is usually around the edges of a school. Like next to the school sign or by the parking lots. It’s not to shade kids in sunny weather.

Nimah Gobir: And these days kids need all the shade they can get. Triple digit temperatures have forced schools all around the country to cancel classes and even delay the first day of school. Here’s what 4th grader Adriana Salas is noticing.

Adriana Salas: It’s mostly hot where we’re playing at. And sometimes when it’s too hot, sometimes when you look like, just on the top of anything it turns like foggy.

Nimah Gobir: She’s talking about when it gets so hot out that the ground looks kind of wavy. She’s seen that happen on her school’s playground. We’ll hear more from Adriana later.

Priya Cook: There’s a lot of communities struggling with urban heat island effect and really extreme temperatures that make it unsafe for kids to be outside.

Nimah Gobir: This is Priya Cook from the Children & Nature Network organization.

Kara Newhouse: I heard Priya say “urban heat island effect.” What is that?

Nimah Gobir: That’s when asphalt and pavement actually increase the temperature in a community.

Priya Cook: There’s a lot of materials that are used in playgrounds that we use in parking lots and roads that really absorb heat and reflect that heat back.

Nimah Gobir: Places that have a lot of urban heat islands are likely to be lower income parts of the city because they usually have fewer plants and more pavement. Often these hotter areas are populated by folks of color.

Priya Cook: There’s a difference in some cases of ten degrees between a place that has trees planted and a site that does not. And so that’s in many cases, that’s a big enough difference to, dictate whether or not kids are going to go outside that day, which has all kinds of health and learning impacts.

Nimah Gobir: The good news is that schools aren’t standing idly by while their schoolyards heat up. We’ll hear from one school in San Leandro, California about how they turned to their schoolyards as a way to learn more about these environmental changes firsthand. That’s coming up after the break.

Nimah Gobir: Stay with us.

Nicole Lamm: Welcome, everybody.

Nimah Gobir: It’s a beautiful day at Roosevelt Elementary School in San Leandro, California. Today it’s 67 degrees fahrenheit, but temperatures here can get into the triple digits. Ms. Heinz and Ms. Lamm’s 4th grade classes have come together to start a project that uses their schoolyard as a 3D textbook.

Nicole Lamm: Today is our first day of doing our “How Cool is Your School?” project.

Nimah Gobir: Ms. Lam is speaking to students using a headset. This project is the brainchild of Green Schoolyards America — Sharon Danks, who we spoke to earlier is the founder of that organization. Ms. Lamm teed up students for the “How Cool is Your School?” project with two guiding questions…

Nicole Lamm: Is our school a comfortable place for children and adults when the weather is warm?

Nimah Gobir: And…

Nicole Lamm: How can our school community take action to shade and protect students from rising temperatures due to climate change?

Nimah Gobir: Students are put into groups of three and each group is given a map of the school

Nicole Lamm: We have our classrooms right here. We have the basketball court, the cafeteria, our other building over there and the kindergarten rooms…

Nimah Gobir: Different locations on the map are numbered from one to 25

Nicole Lamm: Those numbers are there for a reason. You are going to get five places that you have to measure. So you have to figure out exactly where that number is and find that spot in the school.

Nimah Gobir: Each group also gets an infrared thermometer.

Dorie Heinz: You’re going to point the thermometer at the ground. When you pull the trigger, the temperature stops and records it. That’s where you and your team are going to record your temperature. So, at one location you’ll be doing three readings.

Nimah Gobir: This is the crux of the project, so I’ll reiterate what Ms Lamm says: Each group takes three temperature readings of the same point on the ground in their assigned location. This is to get an accurate reading of the ground surface. Then, they record the average of the three readings on a worksheet.

Adrianna Salas: We are going on the field to 16.

Nimah Gobir: We followed one group of students as they did their measurements.

Arlo Jones: Arlo Jones, fourth grade.

Jake Decker: Jake Decker, fourth grade.

Adriana Salas: Adriana Salas, fourth grade.

Nimah Gobir: And yes, that is the same Adriana we heard from earlier!

Nimah Gobir: First up on their list: area 16. It’s located on the field, so it’s a grassy area. They make their way over and get their three readings with the thermometer

Nimah Gobir: They record their findings. The surface of the field has an average of about 97 degrees. They head to the next spot on their list. Number 17 on the map. It has grass too and it’s close to some classrooms.

Nimah Gobir: So the average temperature of the ground surface here is about 95 degrees. They start to make their way to their third location: number 18. It’s a triangular playground area with swings.

Arlo Jones: I would say it’s like the main playground. The main place where people play.

Adriana Salas: It’s like the big playground

Nimah Gobir: They describe it as the school’s main playground so most kids play there. The surface is made of that rubber safety material that you see in so many schoolyards now. Especially newer schools…and they predict that it’s going to be hot. They’re right. The three readings they get there average at a steamy 143 degrees

Nimah Gobir: Adriana shared some reflections on what she’s learned about her schoolyard so far.

Adriana Salas: It’s very hot. And sometimes you might get like, a shocking, like, “Wow. Like kids play in the hotness.”

Nimah Gobir: After students are finished visiting all of the locations they’ve been assigned, they come back to the classroom to talk about their findings.

Nicole Lamm: So when we say a location that you tested, I want you to raise your hand and read out the average that you just found for location one.

Nimah Gobir: That’s Ms. Lamm again. The other teacher, Miss Heinz, is standing in front of a poster-sized map of the school. She has colored stickers ranging from blue – which represent temperatures in the 70s or below – to deep shades of red, which represents temperatures over 100 degrees.

Nicole Lamm: Location two right over here where the tetherball is. 115.

Nicole Lamm: What about location three? Right on the lake by the four square. 123.

Nicole Lamm: Four, which is over by where you eat lunch every day? 63.

Nicole Lamm: What do we notice about location four? It’s covered by a shade structure? And can you say that number nice and loud one more time? Sixty-three degrees is a lot cooler when we have a shaded structure. Interesting to notice.

Nimah Gobir: Every time they call out a number, a colored sticker representing the temperature is stuck to the corresponding location on the big version of the map.

Kara Newhouse: So students could actually see where the different colored dots were clustered at their school.

Nimah Gobir: They went all the way through 25 locations. And when they were all done calling out the average temperatures. They were asked to share what they noticed about all the colored dots on the map.

Nicole Lamm: What do you notice about the two places that are blue, though?

Students: They’re shaded.

Dorie Heinz: They’re shaded so they’re way cooler.

Nicole Lamm: What? Shades the blue dot on this side?

Students: The tree.

Nicole Lamm: What about the other one? The canopy. The shade structure. So both of those are the coolest locations and we know that they have things that are providing shade: the trees and the shade structure. Really good observation.

Nimah Gobir: Aside from those two blue spots the school is mostly a cluster of red and yellow dots representing ground surface temperatures from 80 degrees to as high as 151 degrees. The really hot temperatures are on the playgrounds and basketball courts. Materials like turf, rubber and blacktop receive temperatures in the triple digits.

Nimah Gobir: But the project doesn’t end there.

Kara Newhouse: What else do they do?

Nimah Gobir: A big part of using your school as a 3D textbook, especially when dealing with big issues like climate change, is finding solutions and encouraging student agency. So for the last part of the activity, students make a proposal for how they can make the school a bit cooler. So Ms. Lamm directs the students’ attention back to the big map again.

Nicole Lamm: We want to mark our map with triangles to show where we think we should plant more trees and squares for where we think we need shade structures.

Nimah Gobir: You can hear that they’re thinking about the schoolyards materials as they decide which places need cooling down.

Nicole Lamm: So Adriana is saying that not just because of the ground surface material, but because of the playground itself that could benefit from having a shade structure over it. Is that right?

Adriana Salas: Because the play structure is made out of metal. Metal is really easy to get hot

Nicole Lamm: Right. Thinking about that material again. The play structure is made out of hard plastic and metal. Those things get really really hot. So we definitely want to add a shade structure over the playground. I love that idea. I also heard Adriana say that we want to add a tree to the middle of the field similar to how it looks at the front of the school with our big trees.

Nimah Gobir: When they were done, they put the big map with all of its stickers on display in the front of the school for parents and community members to see.

Kara Newhouse: Sometimes talking about real-world challenges can lead to anxiety and feelings of helplessness, but it’s great that they were able to share their insights. That’s often the first step towards putting ideas into action.

Nimah Gobir: Activities like this can lead to schools developing green schoolyards. Here’s Sharon Danks again to tell us more.

Sharon Danks: I would say that it is most succinctly described as an ecologically rich park.

Nimah Gobir: They vary widely. The plants in a green schoolyard will depend on its ecosystem and climate. A lot of schools are starting to transition to green schoolyards.

Sharon Danks: I think the need is becoming more clear through weather getting more extreme.

Nimah Gobir: California is in the second year of a statewide initiative called the California Schoolyard Forest System. The main goal is to increase the number of trees in public schools.

Nimah Gobir: Green schoolyards don’t just provide shade on hot days. They come with a whole bunch of benefits, including more opportunities for kids to use their schools for learning. When school leaders start dreaming about the potential they can unlock with a green schoolyard, it’s hard to stop. They start saying things like…

Sharon Danks: I’d like a place for kids to do their curriculum outside. I’d like a place that’s good for physical and mental health for kids and teachers. We’d like a place for nature. We’d like a place for the birds to come, the wildlife, to be able to visit the pollinators andyou want to see the butterflies and you know, things like that.

Nimah Gobir: Our school buildings and schoolyards are not just physical spaces but dynamic learning resources waiting to be tapped into.

Kara Newhouse: Learning from textbooks is valuable, but true learning comes alive when we bring education into the real world. School grounds and schoolyards provide the perfect opportunity to do just that.

Nimah Gobir: And if a school is able to develop a green schoolyard, you can provide kids with a living laboratory where they engage with nature, explore ecosystems, and understand the impact of their actions on the environment.

Nimah Gobir: So teachers, you don’t have to travel far for your next hands-on learning opportunity. Seeing your schoolyards and school buildings in a new light might just empower the next generation of change-makers.

Adriana Salas: I think I think now I’m going to be really good – an expert!

Nimah Gobir: This episode would not have been possible without Sharon Danks, Jenny Seydel, Priya Cook, Principal Kumamoto, Ms. Lamm, Ms. Heinz, and their 4th graders. A big thank you to Kevin Stark and Laura Klivans for their support with reporting.

Nimah Gobir: The MindShift team includes Ki Sung, Kara Newhouse, Marlena Jackson Retondo and me, Nimah Gobir. Our editor is Chris Hambrick and Seth Samuel is our sound designer.

Nimah Gobir: Additional support from Jen Chien, Katie Sprenger, Cesar Saldaña and Holly Kernan .

Nimah Gobir: MindShift is supported in part by the generosity of the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation and members of KQED.

Nimah Gobir: Thank you for listening!

Continue reading...